This installation explores some of the sexism and racism that impacted negatively on the life and work of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, whilst acknowledging the strength she drew from her roots in Munich’s Dionysian movement and attitudes as New York’s first punk.

This installation explores some of the sexism and racism that impacted negatively on the life and work of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, whilst acknowledging the strength she drew from her roots in Munich’s Dionysian movement and attitudes as New York’s first punk.

In doing so, the work shifts the accepted reading of the last painting Elsa painted in 1924, Forgotten Like this Parapluie am I by You – Faithless Bernice! Rather than an autobiographical account of a self-pitying victim foreshadowing suicide, Elsa is pointing out specific structural forces that were preventing her from building a career and celebrating her major achievements.

Elsa is defiantly leaving the frame of the art field, stomping on ‘authoritative’ books that are being destroyed by the gushing water from her work Fountain as she goes, a former pet drinking bowl that she kept in her flat with a range of other plumbing objects. Fountain sits on the ‘institutional plinth’ and is sullied by Marcel Duchamp’s pipe placed on top of it. Baroness Elsa declared her found objects as art as early as 1913, including her work Fountain from 1917, and her efforts are only now beginning to be debated and acknowledged within the canon.

Elsa is defiantly leaving the frame of the art field, stomping on ‘authoritative’ books that are being destroyed by the gushing water from her work Fountain as she goes, a former pet drinking bowl that she kept in her flat with a range of other plumbing objects. Fountain sits on the ‘institutional plinth’ and is sullied by Marcel Duchamp’s pipe placed on top of it. Baroness Elsa declared her found objects as art as early as 1913, including her work Fountain from 1917, and her efforts are only now beginning to be debated and acknowledged within the canon.

American poet William Carlos Williams (1883–1963), in his chapter about Baroness Elsa in his autobiography, states that when visiting Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap’s apartment in New York, his eye was caught by a sculpture underneath a glass bell. It appeared to be chicken guts, possibly imitated in wax.

“I was told it was the work of a titled German woman, Elsa von Freytag Loringhoven, a fabulous creature, well past fifty, whom The Little Review was protecting. Would I care to meet her, for she was crazy, it was said, about my work. I wrote, fatally, to Margaret or Jane, saying I wanted to meet the woman. They agreed I was precisely the one who should meet her and defend her. But unfortunately she was at that moment in the Tombs under arrest for stealing an umbrella”.

Her painting is a commentary on her neglect by the art establishment. The handle of the umbrella (‘parapluie’) nestles into the curve of Fountain in the painting, as if stabilising it from a fall, forging a relationship between the two objects that were stolen and involved Baroness Elsa’s neglect.

In his autobiography, and also in a letter to Jane Heap, Williams says that Baroness Elsa was ‘playfully killed by some French jokester, it is said, who turned the gas jet on in her room while she was sleeping. That’s the story’. Given the fact that Williams correctly reported details in his autobiography about the ‘forgotten’ umbrella that appears in Baroness Elsa’s painting and features in the work’s title, his assertion about the possible circumstances surrounding her death deserves more attention.

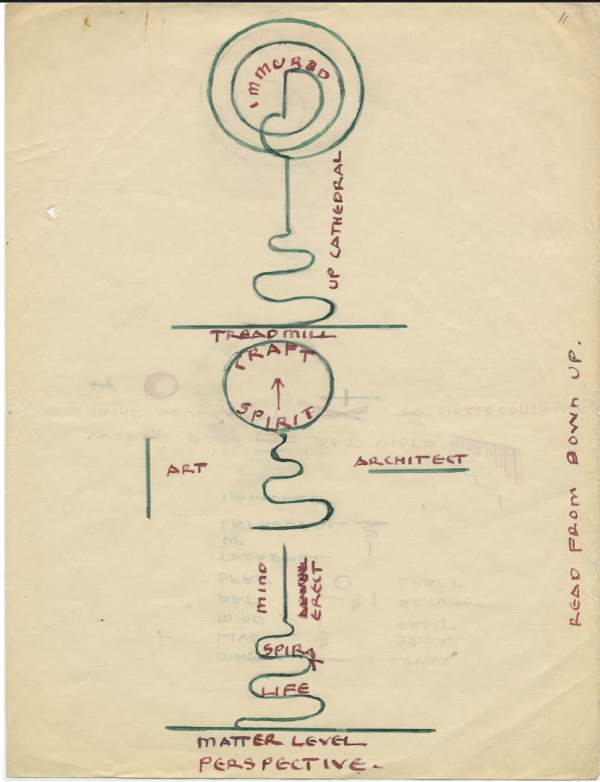

To emphasise that the leg is her own and to show the way in which feminist critique was incorporated into every aspect of her life, Elsa’s poem ‘Matter Level Perspective’ is tattooed onto her leg. Written between 1923 and 1927, the poem shares scientific and mathematical themes with her other work, as well as describing relationships with institutions – including psychiatric ones (SEE BELOW).

“Matter Level Perspective” appears much like a diagram meant to represent moving parts in which words such as “immured,” “craft,” and “spirit” are simply points on an unbroken line in motion. Here, the words are used to emphasize the movement of the lines much like in the machine drawings that Picabia drew for 391 and the Zurich magazine Dada in 1919 and in a special Picabia edition of The Little Review in 1922, in addition to the sketches that Marcel Duchamp used in his notes for The Large Glass. In “Matter Level Perspective,” the Baroness uses sketches that resemble an early Cathode X-Ray tube. The poem begins with “matter” from the “Matter Level Perspective” and continues through the coils or “spiral” of “life” and “art” before coming together as “spirit” and “craft,” but then the break down of these essential elements into their particle and electromagnetic state is the result of the poems movement through the “cathedral,” which functions not only as a play on the word “cathode” and as a comment on the negative affect that institutionalized religion (symbolized by the institution’s edifice itself) has on the spirit and therefore one’s craft but also on the “catholic” rigor of the scientific method for breaking a human down into her particle parts. At the end of the poem, we find the word “immured” trapped and contained in a “circle container” as waves that are still embodied within the circle, but are disembodied from their original “perspective” or form and in danger of being released and therefore disintegrated into the world.

The first page of the first version has the number “2” written in the upper right-hand corner as if it the “final version” had been sent somewhere. In any case, it does nto exist in the manuscript archive. Perhaps, the Baroness sent the poem to Djuna Barnes. It is mentioned in the following letter to Barnes, dated between 1924 and 1927:

. . . WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT: “PERSPECTIVE” – “PERPETUAL MOTION” – AS DRAWINGS? I DO NOT MEAN AS “ART” – IT IS NOT ART – IT IS SIMPLE MATTER OF FACT ILLUSTRATIONS TO MAKE MEANING PLAIN – I LIKED THAT COOL MATTER -OF – FACTNESS ABOUT IT – AND THOUGH ALSO THE TWO DESIGNS IN THEIR PLAINNESS _AS_ DESIGNS – INTERESTING I COULD MAKE THOSE DESIGNS AS THEY _ARE_ – _MUCH_ _MORE_ DELICATE IN _LINE_ – BUT – I HAVE NOT THE MEANS – IN PAPER AND INK – AND SHOULD NEED A CIRCLE. EVEN THESE I SUCCEEDED AFTER MANY BAD TRIALS. DO YOU LIKE THAT “PERSPECTIVE” OF NEARER CONCERN ABOUT FRANCE AND AMERICA? TRUE IT IS – AND NEVER SHOULD I HAVE KNOWN IT -WITH MY TRADITION HAZED EYES – FOR HAVING RETURNED _HERE_! SHALL THAT _CLEAR SIGHT_ COST MY OWN SELF? WHY -FOR _WHAT_ IF _I_ GO AWAY WITH IT? HAPPEN THIS WILL – ANYWAY OF COURSE – BUT WHY MUST _I_ _LEARN_ THAT WIDSOM – AND PERISH FOR IT? x OH DUNA PLEASE I GO IN A CIRCLE – BECAUSE I CAN NOT LET _ROAM_ MY IOMAGINATION FREE – IN JOY! . . . . [UMD reel 2, frame 124]

Irene Gammel’s very different reading of “Matter Level Perspective” describes the form as a body with a head and the spirals resemble sperm-like lines instead of cathode rays. The interplay of scientific and creative forces in this poem, however, also point to themes inspired by Freytag-Loringhoven’s fellow Dadaists. For Dadaists and modernists alike, science and technology functioned in opposition to the elements of chance that were associated with creative impulse. Indeed, technological precision is at the heart of Duchamp’s Large Glass, for which he took meticulous notes on the mathematical and geometric dimensions of the piece. In writing math equations for her poem “Hell’s Wisdom,” the Baroness wrote to Barnes that the poem is “cristall [sic]” in the “conciseness” of its “arithmetic.” Likewise, the Baroness was interested in precision that science and technology afforded.

(The University of Maryland Digital Library Collection)

Further analysis of Elsa’s world are discussed in my article for the online Journal for Artistic Research, Exploring the principles of allodoxic art (in conversation with Baroness Elsa).

(works on paper of pagan imagery in the work are by Paul Venables)