Focussing on the life and legacy of Hannah Arendt, this work shows the importance she placed on the role of ethics, shared action and remembrance as part of community citizenship. Hamburg activist Lena counters the other positions presented in Joseph Beuys’ fictional Tartar rescue, which is extended to include a crash-landing onto Martin Heidegger’s hut. Lena also plays Arendt, mapping her personal experiences in the Gurs prison camp against her theorisation on the importance of poetic thinking for revolutionary action and how remembrance is lost through the dead tradition. Supported by a German government (DAAD) scholarship. Statt Berlin 2013 and Articulate Project Space, Sydney 2015.

SCREEN 1. Joseph Beuys crash lands on Heidegger’s hut to set the story in motion. He describes his journey of redemption. (Projected onto hessian on floor)

SCREEN 2. Hannah Arendt’s project on remembrance is described through her writing on how poetic thinking can provide the tools for revolutionary thinking and how the dead tradition is a form of forgetfulness. (Projected onto monitor under stairs)

SCREEN 3. On the outside wall of Heidegger’s hut is a copy of Arendt’s Heidegger the fox, which describes the trap Heidegger set for others that resulted in his own entrapment. Inside the hut Heidegger indulges in his linguistic tricks to try to explain away his Nazism in his essay The Question Concerning Technology . (Projected onto back wall)

SCREEN 4. On the ferris wheel Hamburg resident Lena finds her will to act when she confronts Harry Lime from the Third Man / Martin Shrekli (American entrepreneur and pharmaceutical executive whose price-gouging activities in 2015 update Lime’s behaviour of selling diluted penicillin to children dying from meningitis). She creates an anti-gentrification project to stimulate interest in the threatened neighbouring Schiller-Oper. (Projected onto felt column wall on platform)

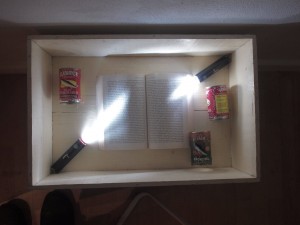

FULL DESCRIPTION: My Burnt Stars installation consists of wall and floor screens depicting both Lena’s activism within the city of Hamburg and more abstract references to the theoretical positions of Hannah Arendt who she also plays in the work. Lena is proactively building community awareness about the rich history and potential of a derelict building, the former Schiller-Oper, by holding events around it. In its first year this was a large street festival. Documentation of the festival, together with the animations projected onto the building as part of it made by Gerald Rocketson and Petronius Amund (Rocket and Wink), are included in Burnt Stars.

The screens also depict exterior scenes of Joseph Beuys’ fictional rescue by the Tartars (Adam Nankervis), which is extended to include a crash landing on the roof of Martin Heidegger’s (Jean Denis Romer) hut. Burnt Stars includes props used in the filming and a version of the hut Heidegger regularly stayed in in Todtnauberg. Like the original, it includes a picture of a young woman from the Black Forest and a wreath. The hut represents Heidegger’s narrow thinking along with his sentimentality about nature and dwelling places, a sentimentality that glorifies the native and excludes the foreign, and which underpins the ethnic chauvinism of Nazism.

The screens also depict exterior scenes of Joseph Beuys’ fictional rescue by the Tartars (Adam Nankervis), which is extended to include a crash landing on the roof of Martin Heidegger’s (Jean Denis Romer) hut. Burnt Stars includes props used in the filming and a version of the hut Heidegger regularly stayed in in Todtnauberg. Like the original, it includes a picture of a young woman from the Black Forest and a wreath. The hut represents Heidegger’s narrow thinking along with his sentimentality about nature and dwelling places, a sentimentality that glorifies the native and excludes the foreign, and which underpins the ethnic chauvinism of Nazism.

The work provides viewers with an experience that creates both maximum juxtaposition and maximum contrast between each of the work’s different representations of being in the world. These are explained further below.

The central motif in the work is the star in various states including when it is hurtling forward when already burnt out. The different representations include light from the torch, a bulb suspended from the ceiling in the Beuys performance, fireworks, stained glass windows, as well as their prismatic effects in the animation sequence that was projected onto the Schiller-Oper as part of Lena’s festival. Another representation is the light bulb from the Marburg building where the young Arendt met her teacher and lover Heidegger in his office, when he left the light on to indicate he was available to see her. The individual performances by all the characters in the film, set theatrically within a Berlin gallery space, provide another thread in the work.

Burnt Stars highlights the importance of linking Arendt’s revolutionary horizon as part of action for the common good.

|

|

-

-

- Continuous and direct civic involvement

-

Arendt’s theory of the political revives Aristotelian categories and distinctions for contemporary political theory. In The Human Condition, she shows the significance of the Greek polis for political action, although not as an exercise in nostalgia. Arendt’s theory of action interprets politics as continuous and direct civic involvement. In doing so, she challenges deeply rooted preconceptions about the nature of politics, which to the liberal mind are the laws and institutions. For Arendt, these merely supply the framework for what she passionately asserts is the essence of politics, namely action. Activities of debate, deliberation, and participation in decision-making, are the focus of Arendt’s politics.

Both Arendt and Aristotle asserted that to be a genuine full member of a community one must be active in its political affairs. No less important is Arendt’s Aristotelian insistence that the public realm is a sphere unto itself, separated by a wide gulf from the interests and desires that make up civil society. By distinguishing the political realm from others, Arendt restores to politics an integrity and dignity that is denied by the liberal tradition, a tradition that views politics as subservient to civil society and the economic.

Arendt’s disagreement with the liberal tradition of politics (since evolved into the neoliberal position) resembles Bourdieu’s allodoxia, as part of his field theory. By stipulating that politics ought to be distinct from the State, Arendt opens up a space to understand Agamben’s observation of the operation of allodoxia between the fields of law and politics. Furthermore, Arendt’s identification of politics as action means that the notion of citizenship must be thought of as participatory, and following from this, that interventions must be thought of as participatory citizen acts.

According to American political scientist academic, Dana R. Villa, the Arendtian ‘renewal of praxis’ has far-reaching implications in both theory and practice for proponents of participatory or decentralised democracy. In his view, her account of action has made it possible to question standard procedural interpretations of democracy and the vocabulary of interests, preferences, and bargaining deployed by pluralist accounts. Best of all, he sees that it facilitates this critique in the name of politics, rather than more problematic notions such as social justice or community.

Arendt almost single-handedly transformed the debate about the nature, tasks, and possibilities of democratic politics. Her recovery of the Greek ideal of the bios politikos enabled participatory democrats to articulate a ‘strong’ democratic politics, a politics grounded on an emphatic distinction between the public and private, one free of the ‘crass instrumentalism’ that colours the liberal view of politics from Hobbes to the present.[1]

Arendt’s legacy of politics as action has been taken up by Lena, dealing with gentrification in her home city of Hamburg*. Lena has initiated and continues to lead a reclamation and restoration campaign to save her neighbouring Schiller-Oper. In my quasi-fictional work, Burnt Stars, Lena plays herself as well as Arendt, and in a carnival scene in contemporary Berlin, she finds her will to act from her encounter with the character Harry Lime from The Third Man, by English filmmaker Carol Reed (1906-1976). Harry Lime in his famous monologue discusses the insignificance of his victims, who are children dying of meningitis from his diluted penicillin. Later in the work American entrepreneur and pharmaceutical executive Martin Shrekli appears in a news item with a short animation sequence illustrating the costs of treatment as a result of his medical drug price gouging activities in 2015.

Arendt’s legacy of politics as action has been taken up by Lena, dealing with gentrification in her home city of Hamburg*. Lena has initiated and continues to lead a reclamation and restoration campaign to save her neighbouring Schiller-Oper. In my quasi-fictional work, Burnt Stars, Lena plays herself as well as Arendt, and in a carnival scene in contemporary Berlin, she finds her will to act from her encounter with the character Harry Lime from The Third Man, by English filmmaker Carol Reed (1906-1976). Harry Lime in his famous monologue discusses the insignificance of his victims, who are children dying of meningitis from his diluted penicillin. Later in the work American entrepreneur and pharmaceutical executive Martin Shrekli appears in a news item with a short animation sequence illustrating the costs of treatment as a result of his medical drug price gouging activities in 2015.

Lena is proactively building community awareness about the rich history and potential of the derelict building by holding events around it. In its first year this was a large street festival. Documentation of the festival, together with the animations projected onto the Schiller-Oper as part of it made by Gerald Rocketson and Petronius Amund (Rocket and Wink), are included in Burnt Stars. Lena is still making plans to save the building. A second festival iteration will include creating a model of it on the street and holding performances that were once held in the building itself. In an update email to me, she discusses recent activities in relation to the future of the Schiller-Oper:

‘It was quite quiet for some time but just a month ago we had a very interesting meeting between the neighbours, the local politicians and some activists from Hamburg. All in all about 30 people. It was organised by a group of elder people that live in a housing project very close by. They invited me as a speaker to talk about the building and its history. The meeting was meant as a first get together to talk and ask about the status quo. Very interesting because it seems that the Oper has been sold twice within the last year and that the new owners are about to talk about their plans in the next two weeks or so. We had very controverse discussions with the politicians and it was a great opportunity to share opinions. So basically I am waiting for the second meeting to see how things are going to continue’.[2]

2. The role of remembrance

Remembrance is an important part of Arendt’s project, although what is original in her work is that her theory of action is a radical anti-traditional exercise and much more than an exercise in renewal, recovery, or retrieval of Aristotelian thought. From Arendt’s perspective, the totalitarian dominations of the twentieth century make the recovery of traditional concepts both impossible and pointless. The main task is to deconstruct and overcome the reifications of dead traditions. As Arendt states: ‘It sometimes seems that [the] power of well-worn notions and categories becomes more tyrannical as the tradition loses its living force and as the memory of its beginning recedes’.[3]

Remembrance is an important part of Arendt’s project, although what is original in her work is that her theory of action is a radical anti-traditional exercise and much more than an exercise in renewal, recovery, or retrieval of Aristotelian thought. From Arendt’s perspective, the totalitarian dominations of the twentieth century make the recovery of traditional concepts both impossible and pointless. The main task is to deconstruct and overcome the reifications of dead traditions. As Arendt states: ‘It sometimes seems that [the] power of well-worn notions and categories becomes more tyrannical as the tradition loses its living force and as the memory of its beginning recedes’.[3]

Burnt Stars illustrates the dead tradition with the 1963 short film, Dinner for One, by German television director Heinz Dunkhase (1928 – 1987). According to the Guinness Book of Records, the English performance of Dinner for One is the most frequently repeated television show ever, although not in Britain. Rather, it is broadcast back-to-back on all channels over the New Year in Germany, even though it has never been shown in Britain. Reporter Philip Oltermann for the Guardian believes that the reason that Germans love Dinner for One may be that it is a funny sketch about something that isn’t funny at all. But in a roundabout way it breaks the greatest German taboo of them all by laughing about the war:

Burnt Stars illustrates the dead tradition with the 1963 short film, Dinner for One, by German television director Heinz Dunkhase (1928 – 1987). According to the Guinness Book of Records, the English performance of Dinner for One is the most frequently repeated television show ever, although not in Britain. Rather, it is broadcast back-to-back on all channels over the New Year in Germany, even though it has never been shown in Britain. Reporter Philip Oltermann for the Guardian believes that the reason that Germans love Dinner for One may be that it is a funny sketch about something that isn’t funny at all. But in a roundabout way it breaks the greatest German taboo of them all by laughing about the war:

‘It is, after all, a comedy that deals in death and meaningless rituals: what has happened to the British and German gentlemen who are no longer with James and Miss Sophie? It allowed Germans to chuckle at a very sinister thought: that history was only ever repeating itself in meaningless loops, that nothing was ever changing’.[4] The inclusion of the film in Burnt Stars also plays with the general nostalgic space old Europe holds of itself and how this crumbles on closer readings of its hegemony.

Arendt’s theory of action can be seen as part of a larger project of ‘remembrance’ through the specific twist she gives this term. Arendt’s ‘remembrance’, as noted by Villa, does not seek to revive concepts as concepts, ‘but to distill them from their original spirit, to arrive at the underlying phenomenal reality concealed by such empty shells’. [5] I present this break with dead tradition in Burnt Stars by using a section of Arendt’s essay on Walter Benjamin, where she describes Benjamin’s ‘poetic’ thinking, a description that Villa says applies equally to her own thought:

‘This thinking, fed by the present, works with the ‘thought fragments’ it can wrest from the past and gather about itself. Like a pearl diver who descends to the bottom of the sea, not to excavate the bottom and bring it to light but to pry lose the rich and the strange, the pearls and the coral in the depths and to carry them to the surface, this thinking delves into the depths of the past-but not in order to resuscitate it the way it was and to contribute to the renewal of extinct ages. What guides the thinking is the conviction that although the living is subject to the ruin of the time, the process of decay is at the same time a process of crystallisation, that in the depth of the sea, into which sinks and is dissolved what was once alive, some things ‘suffer a sea-change’ and survive in new crystallised forms and shapes that remain immune to the elements, as though they waited only for the pearl diver who one day will come down to them and bring them up into the world of the living-as ‘thought fragments’, as something ‘rich and strange’, and perhaps even as everlasting Urphänomene’.[6]

The central motif in the work is the star in various states including when it is hurtling forward when already burnt out. The different representations include light from the torch, a bulb suspended from the ceiling in the Beuys performance, fireworks, stained glass windows, as well as their prismatic effects in the animation sequence that was projected onto the Schiller-Oper as part of Lena’s festival. Another representation is the light bulb from the Marburg building where the young Arendt met her teacher and lover Heidegger in his office, when he left the light on to indicate he was available to see her.

The central motif in the work is the star in various states including when it is hurtling forward when already burnt out. The different representations include light from the torch, a bulb suspended from the ceiling in the Beuys performance, fireworks, stained glass windows, as well as their prismatic effects in the animation sequence that was projected onto the Schiller-Oper as part of Lena’s festival. Another representation is the light bulb from the Marburg building where the young Arendt met her teacher and lover Heidegger in his office, when he left the light on to indicate he was available to see her.

The individual performances by all the characters in the film, set theatrically within a Berlin gallery space, provide another thread in the work. In her role as Arendt, Lena repeats some of the text on remembrance, whilst climbing a two-metre high platform from which prisoners would defecate into large tubs that collected excrement. Setting Arendt’s theorising of poetic thinking against her 1940 experience of the Gurs prison camp in France amplifies the origins of her fears of totalitarianism.

Dinner for One shows how tradition itself is the primary form of forgetfulness, essentially through reification (theorised by Benjamin and Heidegger as well as Arendt).[7] These thinkers all share a sense that the present is peculiarly isolated in a world from which authority, in the form of tradition, has vanished.

Arendt’s form of remembrance aims to intensify our sense of the gap between past and future. For Arendt, what is strongest in the present, what feeds her ‘unhistorical’ thought, is her sense of the rootlessness that in her view made totalitarianism possible. Arendt aims to show how only political action can combat it and the pathologies it creates.

Villa outlines a partly ontological motivation behind Arendt’s theory of action. He sees Arendt’s appropriation of a praxis guided by a desire to recover, not concepts, but a certain way of being-in-the-world, as a central aspect of her critique of modernity and her deconstruction of the Western tradition of political philosophy. Action creates a disclosive relation between plural individuals and their common world, a relation that is constantly threatened by the philosophical/human-all-too-human desire to escape its contingency and groundlessness and find a more stable alternative (politics as technē, as epistēmē, or an instrumentality).[8]

-

-

- Heidegger the fox

-

Heidegger’s thought provides the background for Arendt’s rethinking of the political, yet her appropriation of his work is done in a highly agonistic manner that illustrates a range of exceedingly un-Heideggerian issues. These issues include the nature of political action, the positive ontological role of the public realm, the nature of political judgement, and the conditions for an anti-authoritarian, anti-foundational democratic politics. The Heideggerian project, according to Villa, provides a basis for Arendt’s in three broad areas.

‘First, his book Being and Time provides a conception of human freedom that largely (but not totally) avoids the reductionist, antiworldly tendencies of the subject-centred conceptions of freedom that dominate the tradition. In this regard, Heidegger’s articulation of man’s disclosive relation to Being, and the way in which this relation gets covered over or forgotten, are of critical importance to Arendt’s attempt to theorise political action in nonteleological, open, or ‘anarchic’ terms.

Second, Heidegger exposes, in his subsequent work, the will to mastery and security that underlies the Western metaphysical tradition and that determines the tradition’s conceptualisation of action. Arendt appropriates Heidegger’s deconstruction in order to show how the philosophical hostility to contingency and plurality, to politics, results in a self-conscious reinterpretation of action designed to exclude these dimensions.

Third, and last, Heidegger’s diagnosis of the alienation of the modern age, an alienation rooted in the attempt to cast the subject in a foundational epistemological and ontological role, provides Arendt with the frame for a critique of modernity that illuminates the political consequences of this pervasive subjectification—a critique Heidegger was himself ill-equipped to make. Heidegger seeks to enter a dialogue with the past in order to create a critically powerful bildungsroman (story of education or development). Arendt on the other hand, recasts the tradition in the form of dialogue; it takes the gap or break in tradition as its starting point, as the ‘non-place’ that determines what Arendt calls the ‘contemporary conditions of thought’.[9]

Arendt appropriates themes from Heidegger’s philosophy to aid her struggle against a tradition hostile to plurality, disagreement, and politics itself. But although Heidegger’s deconstruction of the Western philosophical tradition is an invaluable tool, it is no substitute for Arendt’s own phenomenology of action and the public realm.

In Burnt Stars, Berlin-born actor, Jean-Denis Romer, plays Heidegger. Burnt Stars includes a version of the hut Heidegger regularly stayed in in Todtnauberg. Like the original, it includes a picture of a young woman from the Black Forest and a wreath. The hut represents Heidegger’s narrow thinking along with his sentimentality about nature and dwelling places, a sentimentality that glorifies the native and excludes the foreign, and which underpins the ethnic chauvinism of Nazism. Heidegger is well known for his sympathy for Nazism, for which he held an indoctrination session in his hut in 1933.

This part of the installation draws inspiration and energy from the play Totenauberg (Death/Valley/Summit) by German playwright Elfriede Jelinek that premiered at the Vienna Akademie Theatre in 1992. Jelinek explores the relationship between Arendt and Heidegger, using what she calls planes of language (as opposed to dialogue), turning her stage characters into figures of speech. Jelinek’s portrayal of the philosopher Heidegger is based primarily on his essay, written after World War II, The Question Concerning Technology. Gitta Honneger, the translator of this play, says of this essay that ‘he summons up all his linguistic tricks to come to terms with his Nazi utopia’. Honneger describes Jelinek’s skill in the following terms:

‘Etymological transformations to the cheapest puns, Jelinek demonstrates how the rhetoric of the most self-consciously politically, morally, religiously, and fashionably correct picks up on the philosophical and linguistic ‘Heideggerisms’, which easily convert into the slogans of a newly emerging elite of nativism, evolutionary perfectionism, ethnic chauvinism’.[10]

In a corner of my installation in the hut, a 1950s small-screen television represents the opposition to large-scale technology that Heidegger expounded in this essay. A video work plays on it that incorporates glitches to show the fault in the circuit of Heidegger’s thinking. Heidegger, in the water-filled basement of a bomb shelter stares out and repeats ‘I am the fox’. A projection high up on the wall shows excerpts from Dinner for One, as well as an endless loop showing Heidegger in a teepee of denuded trees asking the question ‘The same procedure as last year Miss Sophie?’ Features of a fox’s den line the edges of the shed floor.

On the outside wall of the hut is the following text: ‘Denktagebuch entry by Hannah Arendt, Handwritten July 1953

On the outside wall of the hut is the following text: ‘Denktagebuch entry by Hannah Arendt, Handwritten July 1953

Heidegger says, quite proudly: ‘People say Heidegger is a fox.’ This is the true story of Heidegger the fox.

There once was a fox who was so utterly without cunning that he not only constantly fell into traps but could not even distinguish a trap and a nontrap. This fox had another affliction: something was wrong with his fur, so he was completely lacking in natural protection against the rigors of fox life. After this fox had spent his entire youth hanging around in other people’s traps and not one piece of fur was, so to speak, left unscathed, he decided to completely withdraw from the fox world and began to build a den. With his hair-raising ignorance of traps and non-traps and his incredible experience with traps, he arrived at an idea entirely new and unheard of among foxes: he built himself a trap as a fox den, sat down in it, and pretended it was a normal den (not out of cunning, but because he had always taken the traps of others for their dens), but then decided to become cunning in his own way and arrange his self-made trap, which was only big enough for him, as a trap for others. This again revealed his great ignorance of the trap business: nobody could really fall into his trap, because he was sitting in it himself. This annoyed him; after all, it is common knowledge that, despite all their cunning, all foxes occasionally fall into traps. Why shouldn’t a fox trap – especially one built by the one fox with the most experience with traps – be a match for the traps of men and hunters? Obviously because the trap did not make itself clear enough it was a trap. So our fox hit upon the idea of decking out his trap as beautifully as possible and sticking clear signs all over it that quite plainly said: Everybody come here; here is a trap, the most beautiful trap in the world. From then on, it was quite clear that no fox could ever have strayed into this trap unintentionally. But still, many did come. For this trap served this fox as a den, after all. If one wanted to visit him in the den where he was at home, one had to go into his trap. Of course, everybody could walk right out of it, except him. It was literally the flesh on his bones. But the fox living in the trap said proudly: So many fall into my trap; I have become the best of all foxes. And there was even something true in that: nobody knows the trap business better than he who has been sitting in a trap all his life’.

Heidegger’s life work provided Arendt with the tools for a powerful and convincing critique of his philosophical politics, as her fable illustrates. American literature academic, Leland de la Durantaye, sees Arendt’s depiction of his problem as that of a weakness turned into a strength and that strength then turned against itself.[11] Durantaye sees this passage as an interpretation of Heidegger’s main weakness: ‘His ability to discern logical inconsistencies and metaphysical mystifications, his suspicions about freezing the constant flow of life, thought, and being into the too-rigid forms of concepts and systems left him, like Nietzsche, without a home under the stormy skies of unending change’.[12]

Durantaye turns to the most famous book on political power, where Machiavelli notes: ‘It is necessary to be a fox so as to recognise traps’.[13] Durantaye’s insights reveal how: ‘Heidegger was a fox and recognised traps, but, having isolated and denounced so many homes as traps, as limitations to thought, he found himself in a difficult position when it came time to seek a refuge for himself, and, so the story goes, when he set about to build himself a home he built himself a trap’.[14] This was Heidegger’s rat cunning and the killer instinct, which even went so far as to seek Hitler’s endorsement for a cultural plan to advance his own career.

Some have interpreted this passage as the diatribe of a scorned lover, but the fact that Arendt’s work has equipped advocates of participatory democracy with an effective vocabulary shows otherwise. Arendt’s theory of political action recognises that ‘the self is not and cannot be a premise of politics, but only the precarious achievement of a life lived in a political community animated by a strong sense of shared purpose and identity. […] Arendt’s theory identifies freedom not with an individual’s choice of life-style, but with ‘acting together’ for the sake of the community’.[15]

My Burnt Stars installation consists of wall and floor screens depicting both Lena’s activism within the city of Hamburg and more abstract references to the theoretical positions of Arendt. The screens also depict exterior scenes of Beuys’ fictional rescue by the Tartars, which is extended to include a crash landing on the roof of Heidegger’s hut. Beuys’ landing is not a dead end like Heidegger’s choices, but a turning point where he weaves an alchemical journey of words illustrating the ways in which people incorporate truths and fictions to reconcile life’s negative forces, and how they use creative thinking to enable alternative paths.

My Burnt Stars installation consists of wall and floor screens depicting both Lena’s activism within the city of Hamburg and more abstract references to the theoretical positions of Arendt. The screens also depict exterior scenes of Beuys’ fictional rescue by the Tartars, which is extended to include a crash landing on the roof of Heidegger’s hut. Beuys’ landing is not a dead end like Heidegger’s choices, but a turning point where he weaves an alchemical journey of words illustrating the ways in which people incorporate truths and fictions to reconcile life’s negative forces, and how they use creative thinking to enable alternative paths.

The personal recuperation of Beuys, like my own and others, needs to be contextualised within a larger history, (discussed in more detail in relation to the work of Ray that I apply to the Australian context). This is the discovery and development within the visual arts of dissonant strategies for representing catastrophic history in the aftermath of World War II, and includes a necessary time lag during which the historical disclosures can circulate and fully sink in.

A Spiegel Online International article reported that Beuys admitted in 1980 that he had initially signed up for Hitler’s army out of a ‘feeling of belonging and solidarity with others my age’.[16] Soon after, in 1985, Beuys installed Plight in the Anthony d’Offay gallery in London, the work that was used in Ray’s analysis. Flowing from this, Plight can be considered as a statement of regret for joining the Nazi Party.

In his new search for others with whom he could feel a sense of belonging, Beuys channelled Arendt’s work on political action to find a new being in the world whilst lying on Heidegger’s hut. As a result, Beuys was an exception among demolitionist artists, who tended to confine their practice solely to the art field, as he was instrumental in founding the German Green Party and the Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research.

* The points I raise here are not framed within my broader argument of how Arendt’s thinking on politics can be applied to the social question. See my article for the Journal for Artistic Research from earlier this year, Exploring the principles of allodoxic art (in conversation with Baroness Elsa).

Editors – Jenny Brown and Kat Szuminska

Actors – Lena, Adam Nankervis and Jean Denis Römer

Reclamation and restoration campaigner for the Schiller-Oper, Hamburg and production manager for Schiller-Oper Festival footage:

Lena

Joseph Beuys monologue

JOSEPH BEUYS TRANSFORMER: A Television Sculpture

Director/Producer – John Halpern

Composer – Michael Galasso

Narrative segment – Caroline Tisdall, Exhibition Curator

Filmed at Guggenheim New York 1979

The largest exhibition Beuys created during his lifetime

Distributor – MDS FILMS . COM

Beuys.transformer@mindspring.com

+917.991.9279

Animation sequence and projection of it at the Schiller-Oper Festival used throughout work

www.rocketandwink.com

Historical images

Benjamin Mennerich via the St Pauli Archive – www.st-pauli-archiv.de

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg – www.mkg-hamburg.de

Music at Schiller-Oper Festival

“Ignorance and Poverty” by Martin Campbell played by I-Livity Soundsystem Hamburg

This work has been made possible through the generous support of Sacha Kagan at the Leuphana Universität Lüneburg and the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) scholarship program.

The Schiller in 2023 with link to information about the restoration CAMPAIGN HERE

A gallery walkthrough of Burnt Stars shown at Articulate project space Sydney (2015) that was exhibited previously as a work-in-progress at Stattberlin (2012)). Full individual screen works are above.

A gallery walkthrough of Burnt Stars shown at Articulate project space Sydney (2015) that was exhibited previously as a work-in-progress at Stattberlin (2012)). Full individual screen works are above.

[1] Dana R. Villa. Arendt and Heidegger: The Fate of the Political (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 5.

[2] Lena, email message to author, August 5 2015.

[3] Arendt, Between Past and Future, 14.

[4] The Guardian. “What’s German for funny?” by staff reporter. February 13, 2002. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/feb/12/whats-german-for-funny

[5] Arendt, Between Past and Future, 15.

[6] Hannah Arendt. Men in Dark Times (Orlando: Harcourt Brace and Company, 1968), 205-206.

[7] In her essay on Benjamin, Arendt argues for a similarity between Benjamin’s approach to the past, in which ‘the heir and preserver unexpectedly turns into a destroyer’, and Heidegger’s famous Destruction of the history of ontology, in Section 6 of Being and Time. Villa, in Arendt and Heidegger: The Fate of the Political, claims Heidegger and Benjamin appropriate Arendt in their work on this, but that they all follow Nietzsche’s dictum that ‘the past is understood in terms of what is strongest in the present, or not at all’, 10.

[8] Villa, Arendt and Heidegger: The Fate of the Political, 11.

[9] Villa, Arendt and Heidegger: The Fate of the Political, 13.

[10] Carl Weber (ed.), Drama Contemporary Germany. (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1996), 219.

[11] Leland de la Durantaye. “Being There”, Spring 2007. http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/25/durantaye.php

[12] Cabinet Magazine, “Being There.”

[13] Niccolò Machiavelli. The Prince. (London: Penguin Books, 1999), 84.

[14] Cabinet Magazine, “Being There.”

[15] Villa, Arendt and Heidegger: The Fate of the Political, 7.

[16] Spiegel Online International. “Joseph Beuys: New Letter Debunks More Wartime Myths,” by staff reporter. July 12, 2013. http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/new-letter-debunks-myths-about-german-artist-joseph-beuys-a-910642-2.html